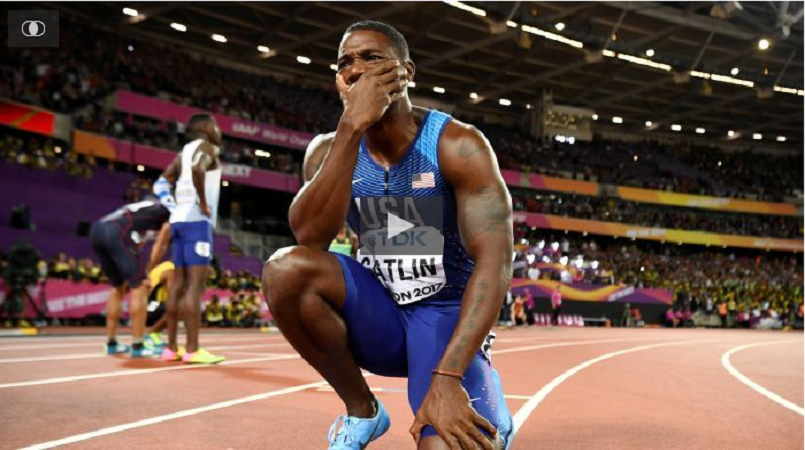

The boos hailed down from every part of the London Stadium. As he knelt down in tears on the track, 56,000 voices jeered him unmercifully. In the outside world, within minutes, his Wikipedia profile had become Justin "the Cheat" Gatlin.

In the history of sport, you were forced to ponder, had there ever been a champion more universally unloved than Gatlin, the twice doping offender who by winning world 100m gold had ruined one of sport's great fairytale farewells?

It was supposed to be all about Usain Bolt.

The idea of the world's greatest athlete not winning his final individual race was like Olivier fluffing his lines in his final Hamlet or Nureyev taking a tumble in his farewell performance of Swan Lake. Unthinkable.

Yet what was really unimaginable, the sport's doomsday scenario almost, was that as the sport's spotless "saviour" was bowing out with his first defeat in any 100m final for four years, it would be the much-maligned Gatlin who would cash in.

Justin Gatlin's career

- Captures US and world indoor 60 metres titles in 2003

- Sprints to 100m title at 2004 Athens Olympics, wins bronze in the 200 and silver in the 4x100 metres relay

- Wins 100m and 200m titles at 2005 world championships in Helsinki

- After returning from four-year doping ban in 2010, wins world indoor 60m title

- Wins 100m bronze in London 2012 Olympics

- Wins 100m silver in 2013 world championships

- Wins 2014 Diamond League final in Brussels with personal best of 9.77 seconds

- Improves personal best to 9.74 in May 2015

- Wins 100m and 200m silvers in 2015 world championships

- Wins 100m silver in 2016 Olympic Games

- Wins 100m gold at 2017 world championships

Doping controversies

- In 2001 at US junior championships, fails doping test for amphetamines found in prescribed medication he had been taking since a child for attention deficit disorder. Is given an early reinstatement by the IAAF the following year but warned a second violation would lead to a life ban.

- Tests positive for male sex hormone testosterone and its precursors at Kansas Relays in April 2006. Details of test do not emerge until Gatlin issues a statement on July 29, 2006. Denies any wrongdoing and his coach claimed the positive test was the result of massage cream containing testosterone being rubbed into his buttocks.

- Accepts initial eight-year suspension, avoiding a lifetime ban in exchange for his cooperation with the doping authorities, and because of the "exceptional circumstances" surrounding his first positive drug test. Ban was reduced to four years by an arbitration panel in December, 2007.

- Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) rejects further appeal in June 2008.

- Returns to action in July 2010 after suspension ends.

Only two years ago, at the Beijing world championships when Bolt outpaced Gatlin for the same title, it was hailed almost as good prevailing over evil.

"He saved his title, he saved his reputation, he may have even saved his sport," screamed Steve Cram, the former 1,500 metres world record holder in the BBC commentary box.

So what had changed two years on?

In a world where drugs offenders are hardly thin on the ground, the 35-year-old American is still the bete noire of the anti-doping lobby, the man who has never shown any remorse and has thus received special opprobrium.

Yet hasn't it reached almost farcical proportions?

On Friday night in the first round, the stadium MC had noted amid all the cat-calling that the pantomime season was Christmas not in August.

No matter; Gatlin was already cast in stone as their villain.

Yohan Blake, who has also served a drugs ban, was cheered to the rafters when he was introduced for the final but Gatlin just remained stony-faced through all the jeering. He has long become used to it. "I tuned it out," he said.

"I did what I had to do. The people who love me are here cheering for me and my fellow countrymen are cheering at home."

Of course, not all Americans will have been, but even Bolt recognised after Gatlin had won in 9.92 seconds, just three-hundredths of a second ahead of him in the bronze medal position, that this reception did not feel fair.

Indeed, in this rarest of defeats, we may have seen the real greatness of Bolt revealed in a way we had never witnessed before.

Yes, the world has loved his once-in-a-century gift and his unmatched showmanship in all his triumphs. They have shown him as a great winner.

Yet here he showed the world how to lose. With grace and honour. And, yes, forgiveness too.

Early in their career, Gatlin had once tried to psyche out Bolt when racing in an adjacent lane by spitting in it.

So right from the start, Bolt could have been forgiven for really having it in for the American.

Yet even when anti-Gatlin feeling was most rife in the sport a couple of years ago, Bolt never sought to rub it in his foe's face.

Who was the first man congratulate Gatlin on Sunday? Of course, it was the Jamaican who went over to hug him with a genuine embrace.

"The first thing he did was congratulate me and say that I didn't deserve the boos," Gatlin revealed.

"He is an inspiration."

Who could argue with his judgement? Even as he contemplated such an anti-climactic end to his individual career, Bolt was big enough to pay a tribute to Gatlin that swam against the tide of ill-feeling.

"He [Gatlin] is a great competitor. You have to be at your best against him," Bolt said.

"I really appreciate competing against him and he is a good person."

Reuters