One of the first refugees “resettled” in Papua New Guinea after leaving Australian-run detention ended up destitute on the streets of Lae before being taken in and given work and accommodation by a local church.

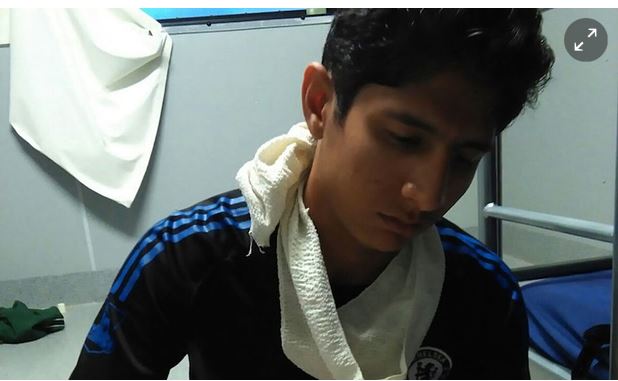

Loghman Sawari, who fled persecution in Iran and was just 17 when he was sent from Australia to the adult men-only Manus Island detention centre in 2013, is one of the first group of six recognised refugees released from detention on Manus and moved to Lae, PNG’s second-largest city.

Sawari, who is now 20, was initially placed in a labouring job with a building company, but after a dispute over pay and an altercation with a housemate he says was motivated by his refugee status, he fled and ended up sleeping rough on the streets of the city.

Lae is riven by particularly high rates of violent crime, according to Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade travel warnings. Assaults using machetes and firearms are common and “it is dangerous to walk the streets, particularly after dark”, according to the Australian government.

Sawari ended up sleeping outside the local police station, where he was found by a group of “street boys”, the local term for young men who roam the city at night, generally committing crime.

The “boys” took him to the local church, where they sometimes sleep, and from there Sawari was given assistance by Bob Butler, the chief financial officer of the Seventh Day Adventist church.

Butler told Guardian Australia that Sawari was now living under his care.

“For the moment, he is OK,” he said. “For the next couple of months he is safe and secure. I have given him a place to live, and a job. After that, it will be up to him what he makes of his situation. But, after some difficulties, he seems to have a good attitude now.”

Butler said Sawari – like many refugees who’ve been displaced for several years – had had an interrupted education and no skills that placed him in demand for employers.

“If you have a skill, or you are entrepreneurial, there are opportunities in PNG. But if you are unskilled, then the pay is very low. Loghman’s problem is that he can’t earn enough money to afford a place for him that is safe.”

Butler is helping Sawari with his health, encouraging him to go jogging and to lift weights. He has also been helping Sawari improve his reading, providing him with books.

“I told him pretty bluntly: the next few years are going to be very tough. Either you make something of your life and things could be good, or they could be really bad. There is no safety net, no support in PNG. If you can’t earn, you have nothing.”

Sawari told Guardian Australia he felt he was being exploited in the job organised for him by PNG immigration. He said was being paid 290 kina – about A$130 – a fortnight, while other workers who were not refugees were paid more.

He said he had been told one year of medical care would be part of his resettlement assistance but his pay was docked for medical expenses when he was in hospital.

Sawari says his housemates – migrant workers but not refugees – “laughed at me because I am refugee”, and told him he was being underpaid because he was a refugee. He said he had a fight with one housemate over cooking in their shared accommodation.

“I had to leave, I could not stay [in] that place.”

Sawari said he feared he would be attacked on the streets, and refused to leave the surrounds of the police station, until he was told by the street boys that the church might be able to help him.